Back to Bedside Project Highlights

Overview

The ACGME is currently funding 30 projects from its initial launch of Back to Bedside in 2018. Read below about the innovative and transformative ideas being implemented. Projects shown here will complete their funding cycle in January 2020. For a list of newly funded projects, visit the 2019 projects list page .

Open Innovations Projects

Institution: Baptist Health – University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Project Title: Minds Matter: Briefing Patients about the Psychiatry Consultation-Liaison Team to Reduce Resistance

Team Leads: Alexander Malati, DO; Sahil Kapoor, MD

The Minds Matter Project is designed to break down the stigma associated with mental health care and establish a therapeutic alliance prior to the psychiatric consultation, to both reduce resistance to care and achieve better outcomes. There is a high prevalence of co-morbid psychiatric conditions in hospitalized patients that exacerbate their presenting concerns, and addressing these symptoms not only improves outcomes but also leads to a better quality of life. To lessen aversion and the impression of being taken by surprise when receiving a psychiatric consult, this project endeavors to establish a relationship with the patient before the appointment. To help patients and their families understand the nature of the consultation and what to expect, residents will provide a pre-consultation fact sheet. This will help reduce patient resistance and apprehension and ultimately improve patient care.

The Minds Matter Project is designed to break down the stigma associated with mental health care and establish a therapeutic alliance prior to the psychiatric consultation, to both reduce resistance to care and achieve better outcomes. There is a high prevalence of co-morbid psychiatric conditions in hospitalized patients that exacerbate their presenting concerns, and addressing these symptoms not only improves outcomes but also leads to a better quality of life. To lessen aversion and the impression of being taken by surprise when receiving a psychiatric consult, this project endeavors to establish a relationship with the patient before the appointment. To help patients and their families understand the nature of the consultation and what to expect, residents will provide a pre-consultation fact sheet. This will help reduce patient resistance and apprehension and ultimately improve patient care.

BROWN UNIVERSITY/RHODE ISLAND HOSPITAL, LIFESPAN

More than Coping with the Pediatric Mental Health Crisis: Basic Therapy and Reflective Tools for Pediatric Residents in the Primary Care Setting

Team Lead: Stephanie Wagner, MD, MPH

The pediatric mental health crisis has emphasized the need for improved behavioral health education and training in pediatric residency programs. This project aims to address this current need via a creation of a curriculum focused on brief psychotherapy skills that can be used in a primary care setting, as well as a creation of a space where residents can process the challenges of being a frontline mental health practitioners. Project evaluation will occur at three points during the project and will also include a reflective, qualitative portion to continue informing future program revisions.

The pediatric mental health crisis has emphasized the need for improved behavioral health education and training in pediatric residency programs. This project aims to address this current need via a creation of a curriculum focused on brief psychotherapy skills that can be used in a primary care setting, as well as a creation of a space where residents can process the challenges of being a frontline mental health practitioners. Project evaluation will occur at three points during the project and will also include a reflective, qualitative portion to continue informing future program revisions.

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA

Mental Health Electronic Medical Record Clinical Tools

Team Lead: Carly Dirlam, MD

Technology is part of modern medicine, but the Back to Bedside project at the University of Minnesota was developed to make it more useful, particularly for psychiatry residents.

The team looked for ways to adapt their current Epic electronic medical record with a toolkit so that clinic visits could go faster, with fewer interruptions to search for information or ask the supervisor questions. By tweaking the database, the team wanted to help residents work smarter and better, worry less about note-taking, and increase meaningful face time with patients.

Among the changes the team made were to incorporate more sources of information and search phrases on medications, including what the medication is used for, potential side effects, how to start it, what to tell the patient, and what lab tests are necessary and when. There are also recommendations for management of certain conditions and patient education and instructions, which can be imported for the After Visit Summary.

Diagnostic interview approaches in the toolkit for specific psychiatric conditions also help save time for residents and guide their patient interactions. And templates for letters to write for different scenarios, such as, for example, when a patient needs a therapy animal or time off work, provide residents with helpful shortcuts.

“This toolkit is introduced in the third year of psychiatry residency when residents do clinic full time,” said Carly Dirlam, MD. “That’s a big transition for residents.”

To help residents get used to the toolkit and its advantages, the team has made presentations to first- and second-year residents to show how useful it can be when dealing with patients.

The toolkit is proving to be a useful expansion of what is traditionally found on the Epic electronic medical record and the school periodically reviews the sources of information and tools to keep it current and timely.

Technology is part of modern medicine, but the Back to Bedside project at the University of Minnesota was developed to make it more useful, particularly for psychiatry residents.

The team looked for ways to adapt their current Epic electronic medical record with a toolkit so that clinic visits could go faster, with fewer interruptions to search for information or ask the supervisor questions. By tweaking the database, the team wanted to help residents work smarter and better, worry less about note-taking, and increase meaningful face time with patients.

Among the changes the team made were to incorporate more sources of information and search phrases on medications, including what the medication is used for, potential side effects, how to start it, what to tell the patient, and what lab tests are necessary and when. There are also recommendations for management of certain conditions and patient education and instructions, which can be imported for the After Visit Summary.

Diagnostic interview approaches in the toolkit for specific psychiatric conditions also help save time for residents and guide their patient interactions. And templates for letters to write for different scenarios, such as, for example, when a patient needs a therapy animal or time off work, provide residents with helpful shortcuts.

“This toolkit is introduced in the third year of psychiatry residency when residents do clinic full time,” said Carly Dirlam, MD. “That’s a big transition for residents.”

To help residents get used to the toolkit and its advantages, the team has made presentations to first- and second-year residents to show how useful it can be when dealing with patients.

The toolkit is proving to be a useful expansion of what is traditionally found on the Epic electronic medical record and the school periodically reviews the sources of information and tools to keep it current and timely.

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS MEDICAL SCHOOL

Mindful Rounding

Team Leads: Emily Levoy, MD; Emily Chen, MD

Sometimes it is hard for residents to find meaning and joy in patient interactions when there are so many demands outside of direct patient care. The Back to Bedside project in the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Pediatric Department was designed to change that.

The goal of the project is two-fold: to promote mindfulness so everyone can be more present during patient encounters; and to identify ways to improve rounding efficiency and allow more time with patients.

“Being present for the moments when we’re directly interacting with patients allows us to be present for the moments of meaning that already exist in our day,” said Emily Levoy, MD.

To teach mindfulness, the leaders held a three-hour workshop during protected teaching time. Interns and senior residents learned what mindfulness is and practiced both mindfulness and mindful communication. With the skills they learned, residents were able to understand how to implement mindful rounding on the floors.

Daily activity cards describing that day’s focus help pediatric residents concentrate on mindful rounding and re-centering themselves between patient encounters. The cards are printed on sticky notes that residents can put on their rolling computer workstations. Examples of such daily activities include focusing on the sensations while washing hands between patient rooms, or taking three deep breaths before entering a patient’s room.

Residents get a new card each day, and if they complete the activity they turn it in with feedback. The project leaders have found that even if residents were somewhat resistant at first, most of them found at least one activity that resonated with them and that they would consider doing on their own.

As the initiative continues, the team plans to make it more sustainable for the pediatric floors and hopefully use it as a model for use in internal medicine and other departments.

Sometimes it is hard for residents to find meaning and joy in patient interactions when there are so many demands outside of direct patient care. The Back to Bedside project in the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Pediatric Department was designed to change that.

The goal of the project is two-fold: to promote mindfulness so everyone can be more present during patient encounters; and to identify ways to improve rounding efficiency and allow more time with patients.

“Being present for the moments when we’re directly interacting with patients allows us to be present for the moments of meaning that already exist in our day,” said Emily Levoy, MD.

To teach mindfulness, the leaders held a three-hour workshop during protected teaching time. Interns and senior residents learned what mindfulness is and practiced both mindfulness and mindful communication. With the skills they learned, residents were able to understand how to implement mindful rounding on the floors.

Daily activity cards describing that day’s focus help pediatric residents concentrate on mindful rounding and re-centering themselves between patient encounters. The cards are printed on sticky notes that residents can put on their rolling computer workstations. Examples of such daily activities include focusing on the sensations while washing hands between patient rooms, or taking three deep breaths before entering a patient’s room.

Residents get a new card each day, and if they complete the activity they turn it in with feedback. The project leaders have found that even if residents were somewhat resistant at first, most of them found at least one activity that resonated with them and that they would consider doing on their own.

As the initiative continues, the team plans to make it more sustainable for the pediatric floors and hopefully use it as a model for use in internal medicine and other departments.

UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Inspire, Mentor, Recognize

Team Leads: Ahmed Khan, MD; Elliot Sultanik, MD

As modern medicine has become increasingly task oriented, the physician-patient relationship often gets pushed into the background. To change that dynamic and return joy and meaning to residents’ daily work, the team at the University of Maryland School of Medicine developed its Back to Bedside project for internal medicine residents as they spend time on the primary cardiology service.

“We wanted to find a way for residents to spend more time at the bedside and improve their connection with patients,” said Ahmed Khan, MD. “This project is designed to decrease burnout and reinvigorate residents and fellows.”

This initiative has three components. The first is Inspire, in which a recognized speaker will talk to fellows and residents about the importance of bedside medicine during departmental grand rounds.

The Mentor part of the project is its core. After morning rounds and duties are finished, a designated cardiology fellow will conduct a half-hour interactive teaching session in a patient’s room in the critical care unit. The fellow uses a white board in the patient’s room to teach pre-selected topics to residents and review physiology and that patient’s echocardiography and symptoms. Not only are residents being educated, the patient is invited to ask questions and learn more about his or her illness.

Installing white boards in patient rooms also gives patients and their families a chance to write down their questions and concerns, which the medical team can answer on morning rounds or during the teaching session. Having patients involved in the educational component of the project and interacting more with their medical team is hoped to also improve satisfaction with their care.

The Recognize part of the project acknowledges the extra time fellows are spending to prepare and conduct these teaching sessions. Their participation is rewarded with a choice of home services, such as Blue Apron meal delivery or maid service, to acknowledge the value of what they’re doing to help train residents and improve their well-being.

As modern medicine has become increasingly task oriented, the physician-patient relationship often gets pushed into the background. To change that dynamic and return joy and meaning to residents’ daily work, the team at the University of Maryland School of Medicine developed its Back to Bedside project for internal medicine residents as they spend time on the primary cardiology service.

“We wanted to find a way for residents to spend more time at the bedside and improve their connection with patients,” said Ahmed Khan, MD. “This project is designed to decrease burnout and reinvigorate residents and fellows.”

This initiative has three components. The first is Inspire, in which a recognized speaker will talk to fellows and residents about the importance of bedside medicine during departmental grand rounds.

The Mentor part of the project is its core. After morning rounds and duties are finished, a designated cardiology fellow will conduct a half-hour interactive teaching session in a patient’s room in the critical care unit. The fellow uses a white board in the patient’s room to teach pre-selected topics to residents and review physiology and that patient’s echocardiography and symptoms. Not only are residents being educated, the patient is invited to ask questions and learn more about his or her illness.

Installing white boards in patient rooms also gives patients and their families a chance to write down their questions and concerns, which the medical team can answer on morning rounds or during the teaching session. Having patients involved in the educational component of the project and interacting more with their medical team is hoped to also improve satisfaction with their care.

The Recognize part of the project acknowledges the extra time fellows are spending to prepare and conduct these teaching sessions. Their participation is rewarded with a choice of home services, such as Blue Apron meal delivery or maid service, to acknowledge the value of what they’re doing to help train residents and improve their well-being.

UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO

Time to Teach: A Time-banking Initiative to Promote Resident-Led Patient Education

Team Lead: Emily Ambrose, MD

In the Back to Bedside project in the Otolaryngology Department at the University of Colorado, residents are engaged in monthly patient education efforts with a goal of increasing patient education both in person and online.

The team publicizes the monthly lecture series through flyers posted in the hospital clinic, as well at the county, VA, and children’s hospitals. The team developed a list of topics in a curriculum to address a range of ENT issues. If residents are receiving a lot of calls about one type of concern, such as sinus infections, that topic might be added to the list. The curriculum is designed to cover general ENT issues of interest and to address common themes and misconceptions.

The resident-delivered lectures are held monthly and run for approximately 45 minutes. As one resident is speaking, another videotapes the lecture and conducts patient surveys on the value of the program, feedback for the resident lecturer, and suggestions for future topics. Following the lecture, the video is posted on the department’s website as a resource for wider viewing.

For residents, participation in delivering lectures or helping with the educational sessions is voluntary, but the team created an incentive: anyone participating in extracurricular activities like these banks “time” and earns credits for the additional work. Credits can then be redeemed for anything from an Amazon gift card to maid service or food delivery. That way, time spent on a scholarly activity gets compensated with rewards that the resident needs and wants.

“We hope that the interaction with patients during the teaching experience, in combination with the time-banking rewards, will help decrease resident burnout and improve workplace satisfaction,” said Emily Ambrose, MD.

In the Back to Bedside project in the Otolaryngology Department at the University of Colorado, residents are engaged in monthly patient education efforts with a goal of increasing patient education both in person and online.

The team publicizes the monthly lecture series through flyers posted in the hospital clinic, as well at the county, VA, and children’s hospitals. The team developed a list of topics in a curriculum to address a range of ENT issues. If residents are receiving a lot of calls about one type of concern, such as sinus infections, that topic might be added to the list. The curriculum is designed to cover general ENT issues of interest and to address common themes and misconceptions.

The resident-delivered lectures are held monthly and run for approximately 45 minutes. As one resident is speaking, another videotapes the lecture and conducts patient surveys on the value of the program, feedback for the resident lecturer, and suggestions for future topics. Following the lecture, the video is posted on the department’s website as a resource for wider viewing.

For residents, participation in delivering lectures or helping with the educational sessions is voluntary, but the team created an incentive: anyone participating in extracurricular activities like these banks “time” and earns credits for the additional work. Credits can then be redeemed for anything from an Amazon gift card to maid service or food delivery. That way, time spent on a scholarly activity gets compensated with rewards that the resident needs and wants.

“We hope that the interaction with patients during the teaching experience, in combination with the time-banking rewards, will help decrease resident burnout and improve workplace satisfaction,” said Emily Ambrose, MD.

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA DAVID GEFFEN SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Upfront Comprehensive Medical Evaluation

Team Lead: Kyle Ragins, MD

A patient goes to the Emergency Department and waits. He tells his story in Triage, then to a nurse, then to a resident, and maybe even another time or two. That’s a lot of waiting and repetition. Unless that patient is visiting UCLA’s Ronald Reagan Medical Center Emergency Department, where a Back to Bedside project is underway.

The project team created the Upfront Comprehensive Medical Evaluation (UCME) to deliver high quality care to patients more efficiently, with fewer repetitions of the story.

With UCME, everyone sees the patient at the very first encounter – nurse, resident, and attending physician – so everyone gets the same information at the same time.

“The advantage for residents is that they don’t have to rehash information for the attending,” said Kyle Ragins, MD. “Now residents are with the attending at the bedside, dealing with them directly and gaining feedback on how the history is taken and how the exam is performed.” This new workflow in the department means residents have more educational opportunities because discussions with attending physicians are much more substantive and focused on specific patient management.

In the ideal scenario, ED patients are seen by the medical team in a triage room and are either assigned to a room, sent back to the Waiting Room to await tests, or admitted to the hospital. When space is limited, sometimes the UCME workflow has to be adjusted, but the foundational elements of the project—everyone seeing the patient together and the first person the patient sees in the ED is a physician—is consistent.

Residents participating in UCME are gaining valuable learning experiences by working more closely with their attending physicians, and getting feedback in real time. That extra education pays off in a more meaningful work experience.

A patient goes to the Emergency Department and waits. He tells his story in Triage, then to a nurse, then to a resident, and maybe even another time or two. That’s a lot of waiting and repetition. Unless that patient is visiting UCLA’s Ronald Reagan Medical Center Emergency Department, where a Back to Bedside project is underway.

The project team created the Upfront Comprehensive Medical Evaluation (UCME) to deliver high quality care to patients more efficiently, with fewer repetitions of the story.

With UCME, everyone sees the patient at the very first encounter – nurse, resident, and attending physician – so everyone gets the same information at the same time.

“The advantage for residents is that they don’t have to rehash information for the attending,” said Kyle Ragins, MD. “Now residents are with the attending at the bedside, dealing with them directly and gaining feedback on how the history is taken and how the exam is performed.” This new workflow in the department means residents have more educational opportunities because discussions with attending physicians are much more substantive and focused on specific patient management.

In the ideal scenario, ED patients are seen by the medical team in a triage room and are either assigned to a room, sent back to the Waiting Room to await tests, or admitted to the hospital. When space is limited, sometimes the UCME workflow has to be adjusted, but the foundational elements of the project—everyone seeing the patient together and the first person the patient sees in the ED is a physician—is consistent.

Residents participating in UCME are gaining valuable learning experiences by working more closely with their attending physicians, and getting feedback in real time. That extra education pays off in a more meaningful work experience.

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA (SAN DIEGO) MEDICAL CENTER

Capturing Dignity

Team Lead: Ali Mendelson, MD

Seeing patients as real people with real lives is a key ingredient in returning the joy and meaning to residents’ work. The Back to Bedside project at the University of California San Diego Medical Center is exploring the use of patient photos as a communication tool to help residents interact with patients on a more personal level.

In this project, patients are asked to bring in an eight by 10 photo of themselves to post above their beds. With a large photo above the bed, the idea is that residents will get a better idea of how that patient sees him/herself and what he/she wants to communicate about him/herself.

Patients have said they like having the photos on the wall and the longer interactions with the medical team the photos can trigger. Providers sometimes pull up a chair and talk to the patient about the photo or its context, which helps the patient feel and be heard.

“The goal is to make this the new standard of care in the palliative care unit, two ICUs, and in one of the medical/surgical units,” said Ali Mendelson, MD. “We believe that getting to know what’s important to our patients will help us make our care fit their goals.”

Part of this Back to Bedside project is studying the effect on resident burnout and whether the photos influence physician-patient interactions. Another part is analyzing the photos the patients choose and why they chose them, so patients will be surveyed about their photo choices, what they wanted to communicate with their photo, and how having the photo above the bed impacted their interactions with the medical team.

Seeing patients as real people with real lives is a key ingredient in returning the joy and meaning to residents’ work. The Back to Bedside project at the University of California San Diego Medical Center is exploring the use of patient photos as a communication tool to help residents interact with patients on a more personal level.

In this project, patients are asked to bring in an eight by 10 photo of themselves to post above their beds. With a large photo above the bed, the idea is that residents will get a better idea of how that patient sees him/herself and what he/she wants to communicate about him/herself.

Patients have said they like having the photos on the wall and the longer interactions with the medical team the photos can trigger. Providers sometimes pull up a chair and talk to the patient about the photo or its context, which helps the patient feel and be heard.

“The goal is to make this the new standard of care in the palliative care unit, two ICUs, and in one of the medical/surgical units,” said Ali Mendelson, MD. “We believe that getting to know what’s important to our patients will help us make our care fit their goals.”

Part of this Back to Bedside project is studying the effect on resident burnout and whether the photos influence physician-patient interactions. Another part is analyzing the photos the patients choose and why they chose them, so patients will be surveyed about their photo choices, what they wanted to communicate with their photo, and how having the photo above the bed impacted their interactions with the medical team.

SCRIPPS MERCY HOSPITAL (CHULA VISTA)

Trainees to the Bedside

Team Lead: Usha Rao, MD

Working in a small hospital in an underserved community can be stressful for family medicine residents, especially when they work in both inpatient and outpatient settings. So, during one of the monthly didactic sessions at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Chula Vista, the Back to Bedside team brainstormed with residents on what makes clinic joyful for them and what makes it stressful.

The team developed a curriculum with eight different lessons to address common stressors. For example, residents noted it was often difficult to manage patients who were very talkative and had many health issues, as they found they were not left with enough time to effectively cover all their concerns. Each resident-led session includes a discussion of tools to help residents deal with what is causing stress in the clinic—in this case, learning how to set an agenda in the room with the patient and using the “what else” technique (i.e., “what else do you want to talk about?”). Following the discussion, residents role-play as doctor and patient to practice the strategies.

While paperwork is an ongoing stress source the team recognizes may not be reducible, they can change their approach to it and have trained residents to work with staff members more efficiently and to understand when and what to delegate.

On the inpatient side, the Back to Bedside team launched bedside rounding for certain patients to help reduce paperwork. While the hospital still uses paper charts, bedside rounding is helping to eliminate some of the extra steps and time while increasing residents’ face time with patients and their families.

“Bedside rounding is a big skill to teach, but we’ve found it was a little less overwhelming to make the change if we just started with new patients and discharge patients,” said Usha Rao, MD. “The goal is to eventually expand bedside rounding to all patients.”

Surveys are being conducted to measure the results of these interventions, but anecdotally, the feedback so far is very positive.

Working in a small hospital in an underserved community can be stressful for family medicine residents, especially when they work in both inpatient and outpatient settings. So, during one of the monthly didactic sessions at Scripps Mercy Hospital in Chula Vista, the Back to Bedside team brainstormed with residents on what makes clinic joyful for them and what makes it stressful.

The team developed a curriculum with eight different lessons to address common stressors. For example, residents noted it was often difficult to manage patients who were very talkative and had many health issues, as they found they were not left with enough time to effectively cover all their concerns. Each resident-led session includes a discussion of tools to help residents deal with what is causing stress in the clinic—in this case, learning how to set an agenda in the room with the patient and using the “what else” technique (i.e., “what else do you want to talk about?”). Following the discussion, residents role-play as doctor and patient to practice the strategies.

While paperwork is an ongoing stress source the team recognizes may not be reducible, they can change their approach to it and have trained residents to work with staff members more efficiently and to understand when and what to delegate.

On the inpatient side, the Back to Bedside team launched bedside rounding for certain patients to help reduce paperwork. While the hospital still uses paper charts, bedside rounding is helping to eliminate some of the extra steps and time while increasing residents’ face time with patients and their families.

“Bedside rounding is a big skill to teach, but we’ve found it was a little less overwhelming to make the change if we just started with new patients and discharge patients,” said Usha Rao, MD. “The goal is to eventually expand bedside rounding to all patients.”

Surveys are being conducted to measure the results of these interventions, but anecdotally, the feedback so far is very positive.

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE

Back to Bedside: Doctors, Let’s do Lunch!

Team Lead: Surein Theivakumar, DO

For busy residents, lunch can often be less about eating than a chance to catch up on leftover morning duties. But the Back to Bedside project at Rush Rehabilitation, a private rehab center at New York University Langone Health, has changed that for residents.

Once a week, Rush rehab residents choose one patient to have lunch with and give their pagers to a senior resident, letting them know of anything urgent to be expected or if there are test results or call backs requiring follow up. Turning over their pagers temporarily removes the junior residents from clinical duties so they can then have an hour for lunch without having the pager going off constantly.

“The goal is to pull residents away from the computers because we spend the majority of our time checking computers, calling consultants, talking to families—and not enough time at the patient’s bedside,” said Surein Theivakumar, DO. “This protected time allows residents to build a personal rapport with patients.”

The project team moved the scheduled lunch out of the patient’s room to a bigger room where both patient and resident can sit at a table in a more social setting and talk about anything they want. Another change made after the resident-patient lunch program began was to inform everyone during morning huddles about the lunch so the staff and nursing could make sure the patient was ready and in the conference room on time.

Prior to beginning, residents were assessed in terms of burnout and overall well-being. After a three-month pilot, a full year of resident-patient lunches is now underway. Initial feedback from residents is that having protected time to interact with patients one-on-one is helping with physician burnout and giving them an overall positive experience.

For busy residents, lunch can often be less about eating than a chance to catch up on leftover morning duties. But the Back to Bedside project at Rush Rehabilitation, a private rehab center at New York University Langone Health, has changed that for residents.

Once a week, Rush rehab residents choose one patient to have lunch with and give their pagers to a senior resident, letting them know of anything urgent to be expected or if there are test results or call backs requiring follow up. Turning over their pagers temporarily removes the junior residents from clinical duties so they can then have an hour for lunch without having the pager going off constantly.

“The goal is to pull residents away from the computers because we spend the majority of our time checking computers, calling consultants, talking to families—and not enough time at the patient’s bedside,” said Surein Theivakumar, DO. “This protected time allows residents to build a personal rapport with patients.”

The project team moved the scheduled lunch out of the patient’s room to a bigger room where both patient and resident can sit at a table in a more social setting and talk about anything they want. Another change made after the resident-patient lunch program began was to inform everyone during morning huddles about the lunch so the staff and nursing could make sure the patient was ready and in the conference room on time.

Prior to beginning, residents were assessed in terms of burnout and overall well-being. After a three-month pilot, a full year of resident-patient lunches is now underway. Initial feedback from residents is that having protected time to interact with patients one-on-one is helping with physician burnout and giving them an overall positive experience.

Project in a Box

Institution: Cleveland Clinic Foundation

Project Title: Healthy Habits Bingo: Playing the Way to Better Health

Team Lead: Marwa Nabil Tarbaghia, MD

Healthy Habits Bingo is a quality improvement and patient safety initiative aimed at fostering collaboration between residents and patients in the outpatient clinic by tracking various health parameters with a goal of promoting improved health outcomes and strengthening the physician-patient relationship through a fun and engaging approach to preventive care. Bingo cards are designed following the recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force. Each card includes a variety of preventive medicine measures. During clinic visits, patients are introduced to the Healthy Habits Bingo concept and offered a card. During each office visit, the bingo cards are reviewed. Completed tasks are recorded and tracked in each patient’s file. Patients accumulate points by completing tasks over multiple visits. Successful completion of a bingo pattern earns the patient a “Health Bingo” status. Patients achieving “Health Bingo” status become eligible for rewards, such as tokens or gift cards, as an incentive for their efforts and progress.

Healthy Habits Bingo is a quality improvement and patient safety initiative aimed at fostering collaboration between residents and patients in the outpatient clinic by tracking various health parameters with a goal of promoting improved health outcomes and strengthening the physician-patient relationship through a fun and engaging approach to preventive care. Bingo cards are designed following the recommendations of the United States Preventive Services Task Force. Each card includes a variety of preventive medicine measures. During clinic visits, patients are introduced to the Healthy Habits Bingo concept and offered a card. During each office visit, the bingo cards are reviewed. Completed tasks are recorded and tracked in each patient’s file. Patients accumulate points by completing tasks over multiple visits. Successful completion of a bingo pattern earns the patient a “Health Bingo” status. Patients achieving “Health Bingo” status become eligible for rewards, such as tokens or gift cards, as an incentive for their efforts and progress.

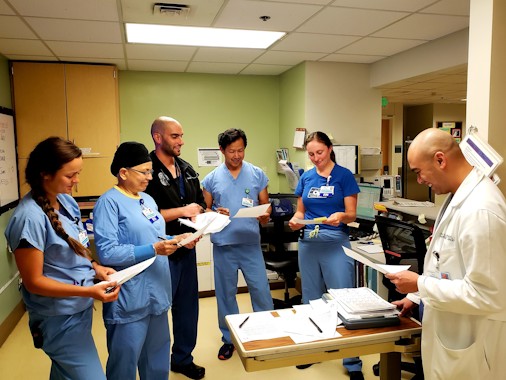

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

Standardizing Evening Bedside Huddles to Promote Patient-Centered Care and Interdisciplinary Teamwork

Team Leads: Kathryn Stadeli, MD; Jay Zhu, MD

The I-Pass hand-off tool is already used for provider-to-provider patient hand-offs at the University of Washington Medical Center. But in an effort to improve communication and teamwork among general surgery night float residents and nurses on acute care surgical floors, the Back to Bedside team there designed an evening bedside huddle initiative.

The night float surgery resident now goes to the nursing stations on floors where most of the acute care surgery patients are located, meets with the charge nurse and any bedside nurses that are available, and discusses the patients labelled as either unstable or needing more observation or acute intervention. The discussion includes both the patient’s current status and their plan. Then the resident/nurse team visits the beside of patients who need an evaluation.

“By improving interdisciplinary teamwork with these regular evening huddles, the goal is to improve both the work environment and patient care,” explained Kathryn Stadeli, MD.

Previously, surgical float residents and nurses were frustrated with poor communication during the evening shift, with both sides feeling like they didn’t have the same information or weren’t on the same page. But by creating this standardized time for provider-nurse communication, the working environment and patient care could be improved.

What started as a two-month pilot on one floor to see how the huddles worked expanded in early winter to two additional surgical floors and is now on track to expand to the final acute care surgical floor. The program has also launched at the area’s county trauma hospital.

Surveys before and after the evening huddles began have shown that both nurses and residents feel communication and teamwork have improved. Some residents noted an improved relationship with evening shift nurses, as well as a decrease in the number of pages they receive, which helps improve their workflow overnight. The annual ACGME Resident Survey questions measuring impact on resident burnout will be analyzed after the sample is large enough.

The I-Pass hand-off tool is already used for provider-to-provider patient hand-offs at the University of Washington Medical Center. But in an effort to improve communication and teamwork among general surgery night float residents and nurses on acute care surgical floors, the Back to Bedside team there designed an evening bedside huddle initiative.

The night float surgery resident now goes to the nursing stations on floors where most of the acute care surgery patients are located, meets with the charge nurse and any bedside nurses that are available, and discusses the patients labelled as either unstable or needing more observation or acute intervention. The discussion includes both the patient’s current status and their plan. Then the resident/nurse team visits the beside of patients who need an evaluation.

“By improving interdisciplinary teamwork with these regular evening huddles, the goal is to improve both the work environment and patient care,” explained Kathryn Stadeli, MD.

Previously, surgical float residents and nurses were frustrated with poor communication during the evening shift, with both sides feeling like they didn’t have the same information or weren’t on the same page. But by creating this standardized time for provider-nurse communication, the working environment and patient care could be improved.

What started as a two-month pilot on one floor to see how the huddles worked expanded in early winter to two additional surgical floors and is now on track to expand to the final acute care surgical floor. The program has also launched at the area’s county trauma hospital.

Surveys before and after the evening huddles began have shown that both nurses and residents feel communication and teamwork have improved. Some residents noted an improved relationship with evening shift nurses, as well as a decrease in the number of pages they receive, which helps improve their workflow overnight. The annual ACGME Resident Survey questions measuring impact on resident burnout will be analyzed after the sample is large enough.

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Meaningful Encounters at the Bedside: A Novel Resident Wellness Program

Team Leads: Jenna Devare, MD; Carl Truesdale, MD

In the hospital, patients are often faced with a sea of white coats that can obscure the humans wearing them. And for residents, making meaningful personal connections with patients is tough. The ACGME Back to Bedside project at the University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers was designed to address these issues.

Developed by and for residents in the Otolaryngology Department, the program includes components at the bedside and away from it. At the bedside, each resident hands out a “trading card” with his or her name and photo on one side, and information about his or her role in treatment, personal history, education, and hobbies on the other. The cards help patients learn more about the residents caring for them, provide a window into the resident’s humanity, and start conversations through the exchange of personal information. Patients seem to like the cards and many collect them like baseball cards.

Away from the bedside, the wellness program includes a post-rotation get together where residents talk about their experiences—both positive and negative—outside of the immediacy of care. This provides an opportunity for a debriefing on patient care, as well as a time for closing and reflecting on residents’ experiences in a rotation.

The goal is to positively affect both residents and patients. The at-the-bedside cards and away-from-the-bedside discussions humanize residents and increase the joy and meaning in their work. At the same time, the program helps patients have a more positive experience in the hospital and improve their opinions of doctors and medical training.

“Burnout is so prevalent in our training and I am fairly confident that 100 percent of our residents experience it during our program,” said Jenna Devare, MD. “I’m hoping that we can bring humanity back to our patients and to ourselves, thereby increasing joy and meaning in our work.”

In the hospital, patients are often faced with a sea of white coats that can obscure the humans wearing them. And for residents, making meaningful personal connections with patients is tough. The ACGME Back to Bedside project at the University of Michigan Hospitals and Health Centers was designed to address these issues.

Developed by and for residents in the Otolaryngology Department, the program includes components at the bedside and away from it. At the bedside, each resident hands out a “trading card” with his or her name and photo on one side, and information about his or her role in treatment, personal history, education, and hobbies on the other. The cards help patients learn more about the residents caring for them, provide a window into the resident’s humanity, and start conversations through the exchange of personal information. Patients seem to like the cards and many collect them like baseball cards.

Away from the bedside, the wellness program includes a post-rotation get together where residents talk about their experiences—both positive and negative—outside of the immediacy of care. This provides an opportunity for a debriefing on patient care, as well as a time for closing and reflecting on residents’ experiences in a rotation.

The goal is to positively affect both residents and patients. The at-the-bedside cards and away-from-the-bedside discussions humanize residents and increase the joy and meaning in their work. At the same time, the program helps patients have a more positive experience in the hospital and improve their opinions of doctors and medical training.

“Burnout is so prevalent in our training and I am fairly confident that 100 percent of our residents experience it during our program,” said Jenna Devare, MD. “I’m hoping that we can bring humanity back to our patients and to ourselves, thereby increasing joy and meaning in our work.”

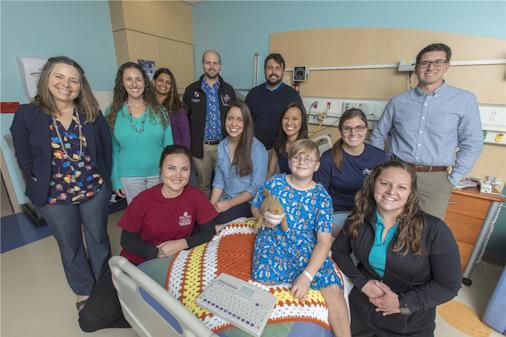

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL

All about Us: Starting the Conversation on Patient and Provider Values

Team Lead: Nicole Nghiem, MD

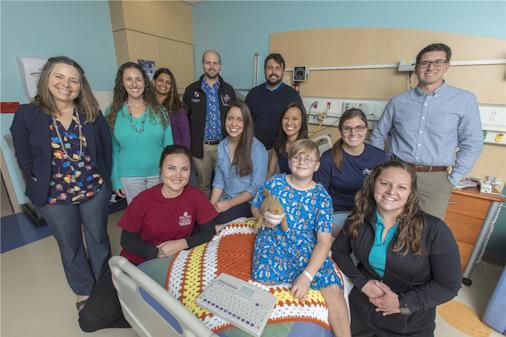

For busy, stressed residents and interns, being able to carve out time to spend with a patient seems like an impossibility. But at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, it’s not only possible but happening, thanks to Back to Bedside.

The project was designed to let members of the ward team take turns each week forwarding their phones to senior residents and not worrying about calls or putting in orders or writing notes. Being able to step away from clinical duties allows the team members to spend time playing with their patients and getting to know them on a deeper level.

One participant said of the opportunity to be that individual who steps away from clinical responsibilities, “This was one of the best days I’ve had.”

Incorporating this program into the hospital’s usual routine forced a bit of a culture shift. The project team needed to make everyone aware that it was a priority, and the ward team members had to help each other get through the day’s tasks so one person could step away. Discussions during pre-rounding have helped the team determine the day’s situation and whether they can get someone back to a patient’s bedside.

This effort to get physicians and patients to see—and understand—each other on a personal level has been in place for nearly a year. Additional plans are also being launched, including letting patients personalize and decorate their rooms with posters, and having the provider team hand out cards with their photos and roles.

“We have to be flexible, because taking good medical care of the children comes first,” said Nicole Nghiem, MD. “But having an opportunity for residents to get away and spend more time with their patients has been very rewarding for them.”

For busy, stressed residents and interns, being able to carve out time to spend with a patient seems like an impossibility. But at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, it’s not only possible but happening, thanks to Back to Bedside.

The project was designed to let members of the ward team take turns each week forwarding their phones to senior residents and not worrying about calls or putting in orders or writing notes. Being able to step away from clinical duties allows the team members to spend time playing with their patients and getting to know them on a deeper level.

One participant said of the opportunity to be that individual who steps away from clinical responsibilities, “This was one of the best days I’ve had.”

Incorporating this program into the hospital’s usual routine forced a bit of a culture shift. The project team needed to make everyone aware that it was a priority, and the ward team members had to help each other get through the day’s tasks so one person could step away. Discussions during pre-rounding have helped the team determine the day’s situation and whether they can get someone back to a patient’s bedside.

This effort to get physicians and patients to see—and understand—each other on a personal level has been in place for nearly a year. Additional plans are also being launched, including letting patients personalize and decorate their rooms with posters, and having the provider team hand out cards with their photos and roles.

“We have to be flexible, because taking good medical care of the children comes first,” said Nicole Nghiem, MD. “But having an opportunity for residents to get away and spend more time with their patients has been very rewarding for them.”

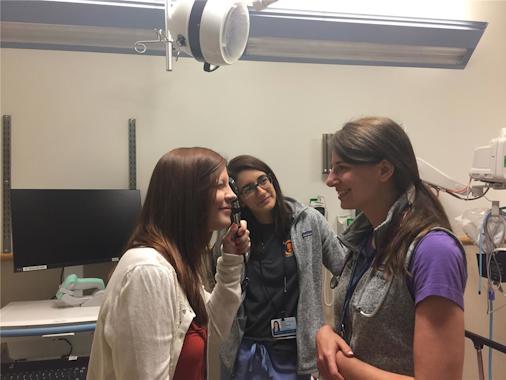

CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL OF PHILADELPHIA

Project SPHERE: Shaping a Patient- and Housestaff-Engaged Rounding Environment

Team Leads: Bryn Carroll, MD; Melissa Argraves, MD; Sanjiv Mehta, MD

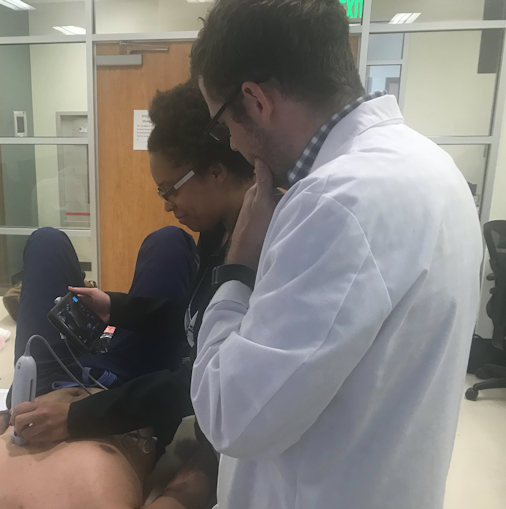

Rounding is a staple of medical education, yet the experience can vary in terms of its benefit to residents. After receiving input from a 50-person group, the ACGME Back to Bedside team at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) looked for ways to make their daily activities more meaningful and bring joy back to their daily tasks. The team’s target was rounding, and they took a quality improvement approach to making changes.

“Primarily rounds take place in the hallway outside the patient’s room. In our initiative, at the beginning of rounds the senior resident, sometimes in conjunction with interns, chooses a patient for a bedside exam,” said Melissa Argraves, MD. “We try to do at least one bedside exam on rounds each day with the whole team.”

The goal is to improve the educational experience for residents, and the team has used the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) quality improvement approach to address not only rounding, but also other areas of educating residents. To increase residents’ time at the bedside, the CHOP team wants residents to take a turn rounding with the attending so they can see some patients one on one and gain insight into how the attending handles both the exam and patient communication.

As the team followed the PDSA approach and analyzed early feedback, one adjustment was already made: having residents complete weekly surveys, instead of daily. With additional data, the team will be able to make improvements to the initiative and determine whether and when to expand to other units.

Rounding is a staple of medical education, yet the experience can vary in terms of its benefit to residents. After receiving input from a 50-person group, the ACGME Back to Bedside team at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) looked for ways to make their daily activities more meaningful and bring joy back to their daily tasks. The team’s target was rounding, and they took a quality improvement approach to making changes.

“Primarily rounds take place in the hallway outside the patient’s room. In our initiative, at the beginning of rounds the senior resident, sometimes in conjunction with interns, chooses a patient for a bedside exam,” said Melissa Argraves, MD. “We try to do at least one bedside exam on rounds each day with the whole team.”

The goal is to improve the educational experience for residents, and the team has used the Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) quality improvement approach to address not only rounding, but also other areas of educating residents. To increase residents’ time at the bedside, the CHOP team wants residents to take a turn rounding with the attending so they can see some patients one on one and gain insight into how the attending handles both the exam and patient communication.

As the team followed the PDSA approach and analyzed early feedback, one adjustment was already made: having residents complete weekly surveys, instead of daily. With additional data, the team will be able to make improvements to the initiative and determine whether and when to expand to other units.

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH MEDICAL CENTER

Addressing Code Status Discussions and Interventions for Vascular Surgeons

Team Leads: Jason Wagner, MD; Alicia Topoll, MD

The patient codes. Now what? Knowing what interventions the patient needs is the easy part. Knowing what interventions the patient actually wants should be just as easy.

Vascular surgery residents at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) launched an ACGME Back to Bedside project to make sure they have those answers.

They are being trained to have code status and end-of-life discussions the first time they sees a patient. “The goal is to make these conversations as routine as finding out what a patient’s allergies are,” said Jason Wagner, MD. “The training is not just ‘how to have the discussion’ but also demystifying and destigmatizing it.”

Training begins with surveys to find out residents’ thoughts on code status discussions and concerns about having them, followed by defining the problems and issues with code status and levels of interventions. Residents talk about various scenarios they might encounter with patients when explaining interventions and code status, as well as how to defuse tough family situations.

Residents role play patient/physician conversations in small groups with a facilitator to simulate the interaction and gain experience in helping patients come to terms with these issues. Residents also practice explaining what could happen in terms of interventions and helping patients arrive at decisions about what they want.

Additional training includes documenting the discussion in the electronic health record so the patient’s preferences can be available to everyone in case there is a code.

Code status documentation rate is reviewed every month, with the eventual goal of having 100 percent documentation. To date, code status conversations with patients are increasing as the entire Vascular Surgery Department at UPMC has been trained, as have everyone in the Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Departments. Now everyone who practices in the school’s Cardiovascular Institute goes through training during initial orientation. And many residents and advanced practice providers have begun documenting code status discussions in clinic, not just when the patient arrives in the hospital.

The patient codes. Now what? Knowing what interventions the patient needs is the easy part. Knowing what interventions the patient actually wants should be just as easy.

Vascular surgery residents at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) launched an ACGME Back to Bedside project to make sure they have those answers.

They are being trained to have code status and end-of-life discussions the first time they sees a patient. “The goal is to make these conversations as routine as finding out what a patient’s allergies are,” said Jason Wagner, MD. “The training is not just ‘how to have the discussion’ but also demystifying and destigmatizing it.”

Training begins with surveys to find out residents’ thoughts on code status discussions and concerns about having them, followed by defining the problems and issues with code status and levels of interventions. Residents talk about various scenarios they might encounter with patients when explaining interventions and code status, as well as how to defuse tough family situations.

Residents role play patient/physician conversations in small groups with a facilitator to simulate the interaction and gain experience in helping patients come to terms with these issues. Residents also practice explaining what could happen in terms of interventions and helping patients arrive at decisions about what they want.

Additional training includes documenting the discussion in the electronic health record so the patient’s preferences can be available to everyone in case there is a code.

Code status documentation rate is reviewed every month, with the eventual goal of having 100 percent documentation. To date, code status conversations with patients are increasing as the entire Vascular Surgery Department at UPMC has been trained, as have everyone in the Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Departments. Now everyone who practices in the school’s Cardiovascular Institute goes through training during initial orientation. And many residents and advanced practice providers have begun documenting code status discussions in clinic, not just when the patient arrives in the hospital.

OREGON HEALTH AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY

Returning the Patient to Medical Conferences: Can We Improve Physician Burnout?

Team Leads: Heather Hoops, MD; Katherine Kelley, MD

“Protected time” during medical conferences is so valuable for residents, boosting learning opportunities without the distractions of pages and clinical duties. At Oregon Health and Sciences University (OHSU), general surgery residents have a new element added to their medical conferences: hearing patients share their experiences.

The goals are to build a stronger relationship between patients and residents as part of the ACGME Back to Bedside initiative, and to help residents feel more comfortable counseling and consenting patients. The first patient-centered conferences have focused on anatomy-altering surgeries, such as ostomies, so residents can gain a greater understanding of the whole process from the patient’s point of view.

Following a shortened didactic portion of the conference, an invited patient shares his or her perspective about everything from what information they received prior to surgery, whether it was helpful, and what the consent process was like. Patients also give residents insight into what life is like after surgery.

“It’s pretty informal. We set it up so patients can tell their story and then we ask specific questions,” said Heather Hoops, MD. “Having the message delivered from patients and families that have gone through it has been pretty powerful. It really sticks with you.”

Faculty members and even residents have helped in recruiting patients or suggesting someone who might be able to contribute to the conference. Another resource is patients who have already agreed to serve as peer-to-peer counselors.

OHSU has a two-year curriculum of these patient-centered didactic resident conferences planned, with four each in the spring and fall. Pre- and post-conference surveys will provide data about residents’ comfort level when counseling patients, but to date the team leaders have reported interest and active engagement by residents in questioning patients.

Conferences after the first year will branch out beyond general surgery patients and may expand to other departments or divisions.

“Protected time” during medical conferences is so valuable for residents, boosting learning opportunities without the distractions of pages and clinical duties. At Oregon Health and Sciences University (OHSU), general surgery residents have a new element added to their medical conferences: hearing patients share their experiences.

The goals are to build a stronger relationship between patients and residents as part of the ACGME Back to Bedside initiative, and to help residents feel more comfortable counseling and consenting patients. The first patient-centered conferences have focused on anatomy-altering surgeries, such as ostomies, so residents can gain a greater understanding of the whole process from the patient’s point of view.

Following a shortened didactic portion of the conference, an invited patient shares his or her perspective about everything from what information they received prior to surgery, whether it was helpful, and what the consent process was like. Patients also give residents insight into what life is like after surgery.

“It’s pretty informal. We set it up so patients can tell their story and then we ask specific questions,” said Heather Hoops, MD. “Having the message delivered from patients and families that have gone through it has been pretty powerful. It really sticks with you.”

Faculty members and even residents have helped in recruiting patients or suggesting someone who might be able to contribute to the conference. Another resource is patients who have already agreed to serve as peer-to-peer counselors.

OHSU has a two-year curriculum of these patient-centered didactic resident conferences planned, with four each in the spring and fall. Pre- and post-conference surveys will provide data about residents’ comfort level when counseling patients, but to date the team leaders have reported interest and active engagement by residents in questioning patients.

Conferences after the first year will branch out beyond general surgery patients and may expand to other departments or divisions.

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS HEALTH SCIENCE CENTER AT SAN ANTONIO

Bedside Therapy

Team Leads: Morgan Hardy, MD

At the San Antonio Military Medical Center, a teaching affiliate of the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Medicine at San Antonio, many patients are younger and healthier, with fewer cognitive issues and less dementia than civilian patients in other facilities. Their in-patient stays may also last longer than in civilian hospitals. That provides an opportunity to expose psychiatry residents to conducting psychotherapy sessions earlier in their education.

“A lot of these young patients in the military are dealing with stage-of-life issues and existential crises,” said Morgan Hardy, MD. “That means we can begin training our interns and residents how to help patients using cognitive behavioral therapy and other therapeutic techniques to improve their sense of self, their relationships, and their sense of the world.”

With a broader social focus on preventing suicides in the military, this ACGME Back to Bedside program is very timely and helpful to both residents and patients. The therapy itself is not novel, but incorporating opportunities for it into the work day is. There is more of an emphasis on therapy so residents have longer interactions with patients and spend more time getting to know them. So over time residents are better able to gauge improvements. The goal is not only to help patients, but also create a more positive learning environment for residents.

The program started with a survey to assess residents’ outlook on and satisfaction with their work. Initially, lecture time on therapy increased, but that was reduced when feedback indicated the extra time was adding to stress. Now more time has been built into the work day for therapy with patients. Following lectures on psychotherapy, residents each pick one patient for weekly therapy sessions.

While initial results for reducing resident stress and burnout appear positive, final data will reveal actual results at the end of a year. Patients are also reporting an appreciation for increased time with doctors and the help they provide. For a lot of patients, therapy to improve their ability to cope can be more valuable than an anti-depressant.

At the San Antonio Military Medical Center, a teaching affiliate of the University of Texas Health Science Center School of Medicine at San Antonio, many patients are younger and healthier, with fewer cognitive issues and less dementia than civilian patients in other facilities. Their in-patient stays may also last longer than in civilian hospitals. That provides an opportunity to expose psychiatry residents to conducting psychotherapy sessions earlier in their education.

“A lot of these young patients in the military are dealing with stage-of-life issues and existential crises,” said Morgan Hardy, MD. “That means we can begin training our interns and residents how to help patients using cognitive behavioral therapy and other therapeutic techniques to improve their sense of self, their relationships, and their sense of the world.”

With a broader social focus on preventing suicides in the military, this ACGME Back to Bedside program is very timely and helpful to both residents and patients. The therapy itself is not novel, but incorporating opportunities for it into the work day is. There is more of an emphasis on therapy so residents have longer interactions with patients and spend more time getting to know them. So over time residents are better able to gauge improvements. The goal is not only to help patients, but also create a more positive learning environment for residents.

The program started with a survey to assess residents’ outlook on and satisfaction with their work. Initially, lecture time on therapy increased, but that was reduced when feedback indicated the extra time was adding to stress. Now more time has been built into the work day for therapy with patients. Following lectures on psychotherapy, residents each pick one patient for weekly therapy sessions.

While initial results for reducing resident stress and burnout appear positive, final data will reveal actual results at the end of a year. Patients are also reporting an appreciation for increased time with doctors and the help they provide. For a lot of patients, therapy to improve their ability to cope can be more valuable than an anti-depressant.

CONNECTICUT CHILDREN’S MEDICAL CENTER

Building Meaning in Work for Residents through Enhanced Communication

Team Leads: Erin Goode, MD; Owen Kahn, MD

Documentation and communication are key to effective patient care. Finding ways to improve both has been the goal of the team at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center.

“We want to have more time to spend with our patients and their families, as well as more time for learning,” said Erin Goode, MD.

In this ACGME Back to Bedside project, one focus has been on improving hand-offs. The documentation side of hand-offs has changed to be more efficient, making pre-rounding time shorter so residents spend less time at the computer and more time at the bedside. Now all the data the residents used to document in multiple places will be entered in a single step.

Accomplishing this meant the co-leader of the team, Owen Kahn, MD, and one of the attendings traveled to Epic Systems headquarters in Wisconsin to learn how to build the system the team envisioned. Having progress notes and the hand-off both in Epic’s electronic health record has reduced the documentation burden—a change that has been rolled out for residents across the hospital, not just in pediatrics.

The team also worked with management to get rid of pagers and transition to a phone app. Without pagers, residents are now on the same communication system as nurses and the rest of the hospital, streamlining what had been an inefficient and time-consuming arrangement.

These efficiencies in documentation and communication have been developed to free up time for residents to spend with patients and return meaning to their work. Some of the program funding has been allocated for activities and projects that residents can do with patients as they gain more time at the bedside. Residents don’t usually have time to play a game or work on an art project with their pediatric patients, but the hope is they now will.

As these improvements are implemented, surveys will track how much time residents are spending with patients and the impact on their well-being.

Documentation and communication are key to effective patient care. Finding ways to improve both has been the goal of the team at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center.

“We want to have more time to spend with our patients and their families, as well as more time for learning,” said Erin Goode, MD.

In this ACGME Back to Bedside project, one focus has been on improving hand-offs. The documentation side of hand-offs has changed to be more efficient, making pre-rounding time shorter so residents spend less time at the computer and more time at the bedside. Now all the data the residents used to document in multiple places will be entered in a single step.

Accomplishing this meant the co-leader of the team, Owen Kahn, MD, and one of the attendings traveled to Epic Systems headquarters in Wisconsin to learn how to build the system the team envisioned. Having progress notes and the hand-off both in Epic’s electronic health record has reduced the documentation burden—a change that has been rolled out for residents across the hospital, not just in pediatrics.

The team also worked with management to get rid of pagers and transition to a phone app. Without pagers, residents are now on the same communication system as nurses and the rest of the hospital, streamlining what had been an inefficient and time-consuming arrangement.

These efficiencies in documentation and communication have been developed to free up time for residents to spend with patients and return meaning to their work. Some of the program funding has been allocated for activities and projects that residents can do with patients as they gain more time at the bedside. Residents don’t usually have time to play a game or work on an art project with their pediatric patients, but the hope is they now will.

As these improvements are implemented, surveys will track how much time residents are spending with patients and the impact on their well-being.

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA MEDICINE

The Face Time Fraction: A Patient-Focused Shift in Emphasizing Empathic Communication and Multidisciplinary Rounding

Team Leads: Kathryn Haroldson, MD; Heath Patel, MD

What a difference a few feet can make. University of North Carolina (UNC) Medicine’s new patient-centered multidisciplinary rounding has moved rounding to the bedside, and patients no longer wonder what the group talking outside their door is discussing. With the launch of the ACGME Back to Bedside initiative, patients are now part of the team, along with the physician, medical students, pharmacist, and nurse.

The new strategy arose out of a desire to increase meaningful face time with patients, as well as to improve physician and patient well-being. With input from the institution’s Patient Advisory Council, the Back to Bedside team knew that patients didn’t like having people standing outside their doors talking and then entering the room to discuss what the team planned to do. “Patients didn’t feel like they were involved and felt that things were being done to them, rather than the plan being developed with them,” explained Kathryn Haroldson, MD.

Initially residents were concerned about making presentations at the patient’s bedside. But the program team created videos to address different scenarios, including differences of opinion or mistakes, involving the patient in the discussion, and handing out Face Sheets with team members’ photos, names, roles, anticipated rounding schedule, and an explanation of what patients can expect during rounds. The videos also demonstrate a key component of this rounding strategy: having the primary communicator sit at eye level for improved patient engagement.

Multidisciplinary bedside rounding was first tested in one medicine service, and has now expanded to all services at UNC. Patients have provided positive feedback, particularly on the Face Sheets and feeling like they are part of their own care team. Residents have found that this new rounding strategy is actually more efficient. It takes less time, which allows them more time to spend with patients or on other duties, or even to get home sooner. They also have a greater understanding of their patients as people.

What a difference a few feet can make. University of North Carolina (UNC) Medicine’s new patient-centered multidisciplinary rounding has moved rounding to the bedside, and patients no longer wonder what the group talking outside their door is discussing. With the launch of the ACGME Back to Bedside initiative, patients are now part of the team, along with the physician, medical students, pharmacist, and nurse.

The new strategy arose out of a desire to increase meaningful face time with patients, as well as to improve physician and patient well-being. With input from the institution’s Patient Advisory Council, the Back to Bedside team knew that patients didn’t like having people standing outside their doors talking and then entering the room to discuss what the team planned to do. “Patients didn’t feel like they were involved and felt that things were being done to them, rather than the plan being developed with them,” explained Kathryn Haroldson, MD.

Initially residents were concerned about making presentations at the patient’s bedside. But the program team created videos to address different scenarios, including differences of opinion or mistakes, involving the patient in the discussion, and handing out Face Sheets with team members’ photos, names, roles, anticipated rounding schedule, and an explanation of what patients can expect during rounds. The videos also demonstrate a key component of this rounding strategy: having the primary communicator sit at eye level for improved patient engagement.

Multidisciplinary bedside rounding was first tested in one medicine service, and has now expanded to all services at UNC. Patients have provided positive feedback, particularly on the Face Sheets and feeling like they are part of their own care team. Residents have found that this new rounding strategy is actually more efficient. It takes less time, which allows them more time to spend with patients or on other duties, or even to get home sooner. They also have a greater understanding of their patients as people.

UNIVERSITY OF BUFFALO JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES

Redefining Meaning in Residency

Team Leads: AnneMarie Laurri, MD; Eric Moss, MD; Regina Makdissi, MD

The Redefining Meaning in Residency project hopes to improve resident satisfaction and burnout through consolidation of education and encouragement of resident responsibility to practice medicine and educate patients. The project will provide afternoon meetings with patients and caregivers to communicate plans and barriers, and educate patients about their disease. The idea for the project grew out of the resident team’s ongoing efforts to improve resident satisfaction and feelings of value. During electronic health record (EHR) downtimes, the residents realized it was very satisfying to talk to patients, nurses, and their colleagues.

“The idea is that establishing a meaningful relationship with the patient is critical for medical residents to develop as physicians,” explained Regina Makdissi, MD, associate director of the University of Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine internal medicine residency program.

By using close-the-loop rounds, the team hopes to educate patients about their health and improve their quality of life. The group also envisions the project expanding to include a series of patient education videos and other easy-to-digest resources to facilitate discussions between provider and patient. Ultimately, the team hopes to create an all-encompassing online resource to help educate patients.

The Redefining Meaning in Residency project hopes to improve resident satisfaction and burnout through consolidation of education and encouragement of resident responsibility to practice medicine and educate patients. The project will provide afternoon meetings with patients and caregivers to communicate plans and barriers, and educate patients about their disease. The idea for the project grew out of the resident team’s ongoing efforts to improve resident satisfaction and feelings of value. During electronic health record (EHR) downtimes, the residents realized it was very satisfying to talk to patients, nurses, and their colleagues.

“The idea is that establishing a meaningful relationship with the patient is critical for medical residents to develop as physicians,” explained Regina Makdissi, MD, associate director of the University of Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine internal medicine residency program.

By using close-the-loop rounds, the team hopes to educate patients about their health and improve their quality of life. The group also envisions the project expanding to include a series of patient education videos and other easy-to-digest resources to facilitate discussions between provider and patient. Ultimately, the team hopes to create an all-encompassing online resource to help educate patients.

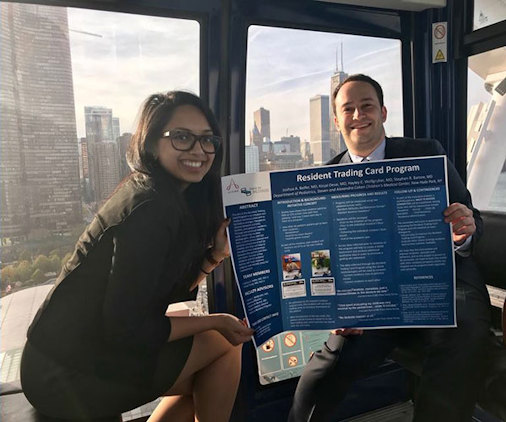

HOFSTRA NORTHWELL SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AT COHEN CHILDREN'S MEDICAL CENTER

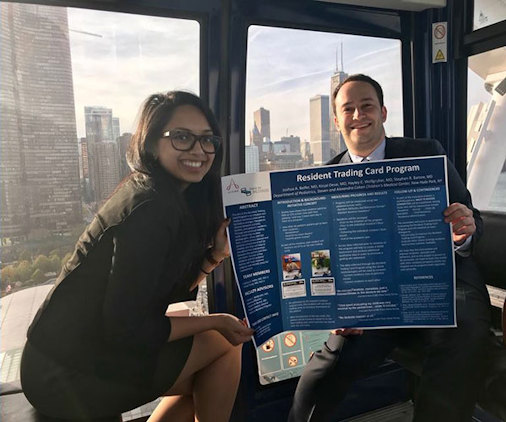

Resident Trading Card Program

Team Leads: Joshua Belfer, MD; Kinjal Desai, MD

The team members at Cohen Children’s Medical Center were inspired to create their project during the winter months of their first year of residency when they started to experience burnout.

“We wanted to do something engaging and exciting that would help us become re-energized at work,” said project co-leader Joshua Belfer, MD, something that reminded us of the reason we went into medicine: our patients.”

The team has created the Resident Trading Card Program, which features cards, similar to baseball cards, with fun pictures of each resident, as well as fun facts, such as favorite ice cream flavor, where the resident is from, and hobbies. The inpatient teams can use these cards to introduce themselves to their patients, who are given the opportunity to create their own trading cards to teach their physicians about who they are and what they like.

The team hopes that by encouraging residents to learn more about their patients outside of their medical conditions, while in turn allowing patients to learn more about them, they’ll reignite their sense of meaning in work.

The team members at Cohen Children’s Medical Center were inspired to create their project during the winter months of their first year of residency when they started to experience burnout.

“We wanted to do something engaging and exciting that would help us become re-energized at work,” said project co-leader Joshua Belfer, MD, something that reminded us of the reason we went into medicine: our patients.”

The team has created the Resident Trading Card Program, which features cards, similar to baseball cards, with fun pictures of each resident, as well as fun facts, such as favorite ice cream flavor, where the resident is from, and hobbies. The inpatient teams can use these cards to introduce themselves to their patients, who are given the opportunity to create their own trading cards to teach their physicians about who they are and what they like.

The team hopes that by encouraging residents to learn more about their patients outside of their medical conditions, while in turn allowing patients to learn more about them, they’ll reignite their sense of meaning in work.

BAYLOR COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

Humanism Rounds: Fighting Physician Burnout through Strengthened Human Connection

Team Leads: Brett Styskel, MD; Reina Styskel, MD